De amigos y parientes -seguramente bien intencionados- he recibido la siguiente invitación: “Se esta haciendo una propuesta desde América Latina, de Venezuela a todos los habitantes de este mundo… para que apaguemos los focos, los bombillos , las luminarias, como se llamen, los televisores , las radios, las computadoras, todo aparato eléctrico o que genere consumo de energía…. el próximo X de abril de 2007 a las 7.53 p.m. por sólo 7 minutos, cada país en su horario. En ese tiempo nos uniremos en una oración por la paz y el amor universal. Esto produciría un efecto psicológico mundial de fraternidad y hermandad”; y hasta aquí la cosa no pasaba de parecer un mero New Age touchie feelie. Pero luego aparece el peine porque la invitación dice que también producirá “un gran ahorro de energía…se propone apagar todas las luces para darle un respiro al planeta. Si la respuesta es masiva, el ahorro energético puede ser brutal”.

De amigos y parientes -seguramente bien intencionados- he recibido la siguiente invitación: “Se esta haciendo una propuesta desde América Latina, de Venezuela a todos los habitantes de este mundo… para que apaguemos los focos, los bombillos , las luminarias, como se llamen, los televisores , las radios, las computadoras, todo aparato eléctrico o que genere consumo de energía…. el próximo X de abril de 2007 a las 7.53 p.m. por sólo 7 minutos, cada país en su horario. En ese tiempo nos uniremos en una oración por la paz y el amor universal. Esto produciría un efecto psicológico mundial de fraternidad y hermandad”; y hasta aquí la cosa no pasaba de parecer un mero New Age touchie feelie. Pero luego aparece el peine porque la invitación dice que también producirá “un gran ahorro de energía…se propone apagar todas las luces para darle un respiro al planeta. Si la respuesta es masiva, el ahorro energético puede ser brutal”.

Así que ya se ve la propuesta va más allá de hermanar al mundo a tientas; es evidente que la misma sirve a una agenda política bien conocida. A ese respecto, mi amigo el filósofo Edward Hudgins, de

The Objectivist Center ha escrito algo muy atingente:

New Cult of Darkness

Edward Hudgins

Since early men ignited the first fires in caves, the unleashing of energy for light, heat, cooking and every human need has been the essence and symbol of what it is to be human. The Greeks saw Prometheus vanquishing the darkness with the gift of fire to men. The Romans kept an eternal flame burning in the Temple of Vesta. Our deepest thoughts and insights are described as sparks of fire in our minds. A symbol of death is a fading flame; Poet Dylan Thomas urged us to “rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

Thus a symbol of the deepest social darkness is seen in the recent extinguishing of the lights of cities across Australia and in other industrialized countries, not as a result of power failures or natural disasters, not as a conscious act of homage for the passing of some worthy soul, but to urge us all to limit energy consumption for fear of global warming.

This is not the symbol of the death but, rather, of the suicide of a civilization.

Certainly most of the individuals turning off their lights saw their acts in a narrower perspective. They have been told by every media outlet that the warming of the earth’s atmosphere due to human activities will certainly cause a global catastrophe unless we act now to radically curtail our energy use. The case for disaster is still weak; but this matter, which deserves dispassionate and serious consideration, is being hyped like the problematic products aimed at an attention deficit disordered audience by the entertainment industry and by pandering politicians.

In our individual lives it is quite rational to want the most for the least. We want the highest quality food, automobiles, and houses for the lowest price. And we want to pay as little as possible to run our cars, heat our homes, and power our consumer electronics. This means we want to waste as little as possible because waste is money that could be spent on other needs. So turning off the lights in an unused room is an act of self-interest.

The goal of our actions should always be our own welfare. And in a fundamental sense, this means using the material and energy in the world around us for our own well-being. The means for doing so is the exercise of our rational minds, to discover how to light a fire, to create a dynamo to generate electricity by burning fossil fuels or to tap the inexhaustible energy of the atom. The standard by which to choose which means is best is economics. In a free market, if producers can generate a kilowatt of power for pennies by burning oil compared to dollars per kilowatt through windmills and solar panels, it makes no sense to use the latter.

Some will argue that the full costs of each means must take account of unintended adverse consequences such as pollution that measurably harms our lives, health, and property. But there are means for dealing with such externalities — usually involving a strict application of property rights — that will not harm us far more than the alleged ills they aim to alleviate by dampening creative human activities and innovations.

When the costs of generating energy via oil rises too high as supplies dwindle — still many decades if not centuries away — our creative minds in a free market will develop less costly ways to harness wind, wave, and sunlight.

Through short-sightedness, sloppy thinking, emotional indulgence and even a deep malice, many environmentalists today — especially in their approach to global warming — are perpetuating an ethos of darkness. Consider the harm of their symbolic acts, to say nothing of the policies many of them advocate.

Most individuals acquire their values through the culture, often through implicit messages that they do not subject to rational analysis. The implicit message for many of turning off the lights of a city is that we should feel guilty for the act of being human, that is, for altering and employing the environment for our own use.

In her novel Atlas Shrugged Ayn Rand describes the consequences of such an assumption in the view from a plane flying over a collapsing country:

“New York City . . . rose in the distance before them, it was still extending its lights to the sky, still defying the primordial darkness . . . The plane was above the peaks of the skyscrapers when suddenly . . . as if the ground had parted to engulf it, the city disappeared from the face of the earth. It took them a moment to realize . . . that the lights of New York had gone out.”

We must keep focused clearly on the fundamental issues in every discussion about the environment: the right of individuals to pursue their own well-being as they see fit; the requirement that man the creator utilize the material and energy in the environment to meet his needs; the rational exercise of our minds as the way to discover the best means to do so; and the exercise of that capacity as a source of pride and self- esteem

The spectacle of a city skyline shining at night is the beauty of millions of individuals at their most human.

Energy is not for conserving; it is for unleashing to serve us, to make our lives better, to allow us to realize our dreams and to reach for the stars, those bright lights that pierce the darkness of the night.

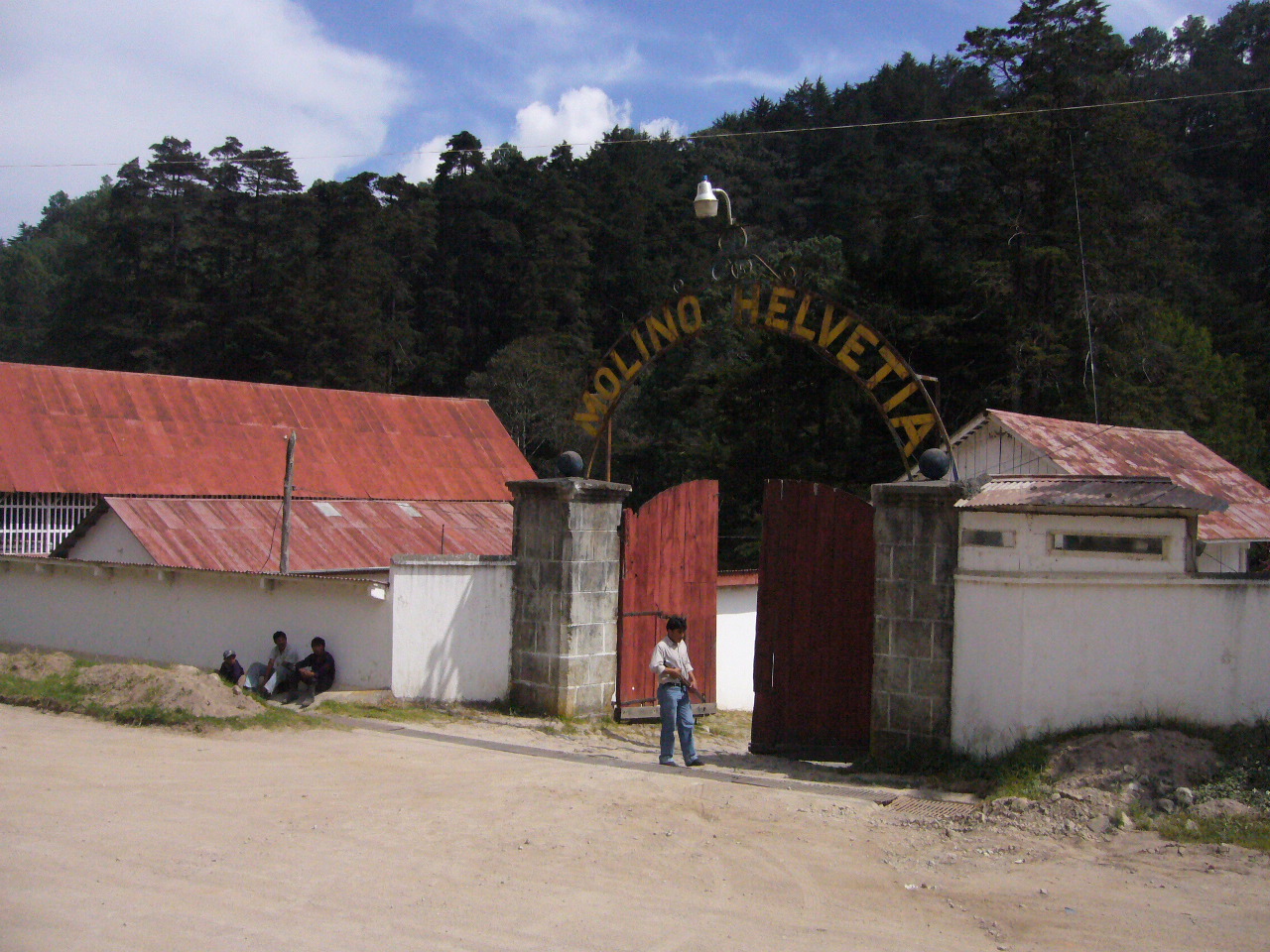

La foto es de la

NASA y muestra la Tierra de noche. Si usted mira con atención, confirma evidentemente el punto de Hudgins.